After getting a bit of hang over the standard C pwnables in CTFs, I was eager to see how this would work in the real world. So I tried starting of with browser pwn. I actually looked at CTFs challenges and though they are not exactly real world I guess they are the closest to it other than actually digging at old CVEs.

Anyway, for the past few days I was trying blazefox from blazeCTF 2018. In this post though, I’ll be writing about some SpiderMonkey data structures that were required to be understood. In this post I’ll only be focusing on SpiderMonkey (Mozilla’s JavaScript engine)

Before starting, I want to say that much of the content is from the references and this post is more or less about my fiddling with what was mentioned there :P

Building SpiderMonkey

To experiment with SpiderMonkey, you might want to build a js shell first. A JS shell is basically a js interpreter. The build instructions can be found here. I am including it below for reference -

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

hg clone http://hg.mozilla.org/mozilla-central spidermonkey

cp configure.in configure && autoconf2.13

mkdir build_DBG.OBJ

cd build_DBG.OBJ

../configure --disable-debug --disable-optimize #

make ## or make -j8

cd dist/bin/

./js

PS: I first came accross this on this cool post by brucechen

Note: I am disabling the debug option as this will add many assertions that will break our exploit, once we get to that part but if you are building to just play around then you should probably enable it.

Representing Values

Most of this section is based on this phrack article. The author explains everything pretty clearly and it is definitely worth a read.

JSValue

In JavaScript we can assign values to variables without actually defining their “type”. So we can do a="this is a string" or a=1234 without specifying int a, char a etc like in C. So how does JS kepp track of the datatype of a variable?

Well, all “types” of data are represented as objects of JS::Value. JS::Value or jsval represents various types in by encoding the “type” as well as the “value” in one unit.

In a jsval the top 17 bits are for the tag that represent what is type of the jsval. The lower 47 bits are for the actual value.

Let’s see this with an example. Run the js shell and create an create an array to hold values of different types -

1

2

js> a=[0x11223344, "STRING", 0x44332211, true]

[287454020, "STRING", 1144201745, true]

So our array is like - [int, string, int, Boolean]. Now lets attach gdb to this and see how these look in the memory…

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

gdb -p $(pidof js)

gdb-peda$ find 0x11223344 # Searching for the array - all elements will lie consecutively

Searching for '0x11223344' in: None ranges

Found 1 results, display max 1 items:

mapped : 0x7f8e531980d0 --> 0xfff8800011223344

gdb-peda$ x/4xg 0x7f8e531980d0

0x7f8e531980d0: 0xfff8800011223344 0xfffb7f8e531ae6a0

0x7f8e531980e0: 0xfff8800044332211 0xfff9000000000001

So the int 0x11223344 is stored as 0xfff8800011223344. Here is the relevant code from js/public/Value.h

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

enum JSValueType : uint8_t

{

JSVAL_TYPE_DOUBLE = 0x00,

JSVAL_TYPE_INT32 = 0x01,

JSVAL_TYPE_BOOLEAN = 0x02,

JSVAL_TYPE_UNDEFINED = 0x03,

JSVAL_TYPE_NULL = 0x04,

JSVAL_TYPE_MAGIC = 0x05,

JSVAL_TYPE_STRING = 0x06,

JSVAL_TYPE_SYMBOL = 0x07,

JSVAL_TYPE_PRIVATE_GCTHING = 0x08,

JSVAL_TYPE_OBJECT = 0x0c,

/* These never appear in a jsval; they are only provided as an out-of-band value. */

JSVAL_TYPE_UNKNOWN = 0x20,

JSVAL_TYPE_MISSING = 0x21

};

----

JS_ENUM_HEADER(JSValueTag, uint32_t)

{

JSVAL_TAG_MAX_DOUBLE = 0x1FFF0,

JSVAL_TAG_INT32 = JSVAL_TAG_MAX_DOUBLE | JSVAL_TYPE_INT32,

JSVAL_TAG_UNDEFINED = JSVAL_TAG_MAX_DOUBLE | JSVAL_TYPE_UNDEFINED,

JSVAL_TAG_NULL = JSVAL_TAG_MAX_DOUBLE | JSVAL_TYPE_NULL,

JSVAL_TAG_BOOLEAN = JSVAL_TAG_MAX_DOUBLE | JSVAL_TYPE_BOOLEAN,

JSVAL_TAG_MAGIC = JSVAL_TAG_MAX_DOUBLE | JSVAL_TYPE_MAGIC,

JSVAL_TAG_STRING = JSVAL_TAG_MAX_DOUBLE | JSVAL_TYPE_STRING,

JSVAL_TAG_SYMBOL = JSVAL_TAG_MAX_DOUBLE | JSVAL_TYPE_SYMBOL,

JSVAL_TAG_PRIVATE_GCTHING = JSVAL_TAG_MAX_DOUBLE | JSVAL_TYPE_PRIVATE_GCTHING,

JSVAL_TAG_OBJECT = JSVAL_TAG_MAX_DOUBLE | JSVAL_TYPE_OBJECT

} JS_ENUM_FOOTER(JSValueTag);

----

enum JSValueShiftedTag : uint64_t

{

JSVAL_SHIFTED_TAG_MAX_DOUBLE = ((((uint64_t)JSVAL_TAG_MAX_DOUBLE) << JSVAL_TAG_SHIFT) | 0xFFFFFFFF),

JSVAL_SHIFTED_TAG_INT32 = (((uint64_t)JSVAL_TAG_INT32) << JSVAL_TAG_SHIFT),

JSVAL_SHIFTED_TAG_UNDEFINED = (((uint64_t)JSVAL_TAG_UNDEFINED) << JSVAL_TAG_SHIFT),

JSVAL_SHIFTED_TAG_NULL = (((uint64_t)JSVAL_TAG_NULL) << JSVAL_TAG_SHIFT),

JSVAL_SHIFTED_TAG_BOOLEAN = (((uint64_t)JSVAL_TAG_BOOLEAN) << JSVAL_TAG_SHIFT),

JSVAL_SHIFTED_TAG_MAGIC = (((uint64_t)JSVAL_TAG_MAGIC) << JSVAL_TAG_SHIFT),

JSVAL_SHIFTED_TAG_STRING = (((uint64_t)JSVAL_TAG_STRING) << JSVAL_TAG_SHIFT),

JSVAL_SHIFTED_TAG_SYMBOL = (((uint64_t)JSVAL_TAG_SYMBOL) << JSVAL_TAG_SHIFT),

JSVAL_SHIFTED_TAG_PRIVATE_GCTHING = (((uint64_t)JSVAL_TAG_PRIVATE_GCTHING) << JSVAL_TAG_SHIFT),

JSVAL_SHIFTED_TAG_OBJECT = (((uint64_t)JSVAL_TAG_OBJECT) << JSVAL_TAG_SHIFT)

};

The code is pretty easy to understand

- Each type (Int, String, Boolean etc) is represented by a number as shown in the enum

JSValueType - This is bitwise or’ed with

JSVAL_TAG_MAX_DOUBLEas shown in the enumJSValueTag. This or’ed value is actually the “tag” that will be used in the final representation. - The 17 bit tag is made to 64 bits by right shifting it by 47 bits.

So the tag for int would be

(1 | 0x1FFF0) « 47 = 0xfff8800000000000

The value of the actual int is or’ed with this tag and stored as ‘0xfff8800011223344’ in the memory.

JSObject

Ok, so that was about representing values. But JavaScript also has various types of “objects”, like arrays. Objects tend to have “properties” -

1

obj = { p1: 0x11223344, p2: "STRING", p3: true, p4: [1.2,3.8]};

In the above example p1, p2, p3 and p4 are “properties” of the object obj. They are like python dictionaries. Each property has a value mapped to it. This can be of any type, int, string, Boolean, object etc. Such objects are represented in the memory as objects of the JSObject class.

The following is an abstraction of the NativeObject class, which inherits the JSObject among other class -

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

class NativeObject

{

js::GCPtrObjectGroup group_;

void* shapeOrExpando_;

js::HeapSlot *slots_;

js::HeapSlot *elements_;

};

Lets discuss each of these fields with some more detail.

group_

I did not fully understand the requirement and the use of the group_ member but I did come across the following comment in js/src/vm/JSObject.h

The |group_| member stores the group of the object, which contains its prototype object, its class and the possible types of its properties.

~I would be glad if anyone could explain more about this field.~ (Updated now)

The group_ member is essentially a member of the ObjectGroup class, with the following members.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

/* Class shared by objects in this group. */

const Class* clasp_; // set by constructor

/* Prototype shared by objects in this group. */

GCPtr<TaggedProto> proto_; // set by constructor

/* Realm shared by objects in this group. */

JS::Realm* realm_;; // set by constructor

/* Flags for this group. */

ObjectGroupFlags flags_; // set by constructor

// If non-null, holds additional information about this object, whose

// format is indicated by the object's addendum kind.

void* addendum_ = nullptr;

Property** propertySet = nullptr;

The comments more or less explain the use of each of the fields, but let me just go into the clasp_ member as it provides interesting targets for exploitation.

Like the comments says, this defines the JSClass that is shared by all objects that belong to this group and can be used to identify this group. Let’s take a look at the Class structure.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

struct MOZ_STATIC_CLASS Class

{

JS_CLASS_MEMBERS(js::ClassOps, FreeOp);

const ClassSpec* spec;

const ClassExtension* ext;

const ObjectOps* oOps;

:

:

}

I did not understand much of the other properties except the ClassOps, but I’ll update it here once I do. ClassOps is basically a pointer to a structure that holds a number of function pointers that define how specific operations on an object take place (!? Lol, don’t worry, example coming right up!). Let’s take a look at this ClassOps structure

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

struct MOZ_STATIC_CLASS ClassOps

{

/* Function pointer members (may be null). */

JSAddPropertyOp addProperty;

JSDeletePropertyOp delProperty;

JSEnumerateOp enumerate;

JSNewEnumerateOp newEnumerate;

JSResolveOp resolve;

JSMayResolveOp mayResolve;

FinalizeOp finalize;

JSNative call;

JSHasInstanceOp hasInstance;

JSNative construct;

JSTraceOp trace;

};

For example the function pointer in the addProperty field, defines which function is to be called when a new property is called. This is all explained pretty nicely in this post. Its a really great article especially for someone starting out with SpiderMonkey exploitation and the author explains everything from scratch. So back to the point, we basically have an array of function pointers here. If we manage to overwrite any of them, we can convert an arbitrary write into arbitrary code execution.

But wait its not that easy. The thing is that this region which contains the function pointers is an r-x region (no write access). But, provided that we have arbitrary write, we can easily fake the entire ClassOps structure and overwrite the pointer to the actual ClassOps in the group field with a pointer to our fake structure.

Thus we have here a means to get code execution provided we have arbitrary write. This will be handy later!

shape_ and slots_

So how does js keep track of the properties of an object? Just consider the following snippet.

1

2

3

obj = {}

obj.blahblah = 0x55667788

obj.strtest = "TESTSTRING"

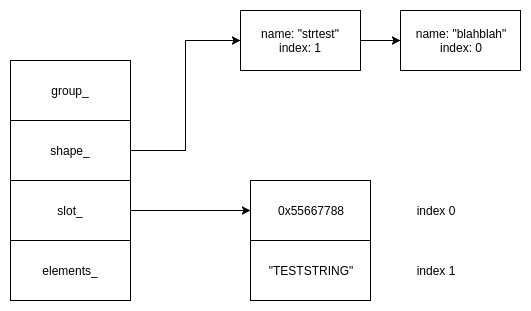

obj is an array but it has a couple of properties as well. Now we js has to keep track of the property names as well as their values. For this it uses the shape_ and the the slots_ field of the object. The slots_ field is the one that contains the values that are associated with each property. It is basically an array that contains only the values (no names). The shape_ contains the name of the property as well as an index into the slots_ array where the value for this property will be present.

Maybe the following pic explains better than I do :)

Okay, so lets a look at what’s happening in the memory with gdb.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

gdb-peda$ x/4xg 0x7f7f01b90120

0x7f7f01b90120: 0x00007f7f01b8a310 0x00007f7f01bb18d0 ----> shape_

0x7f7f01b90130: 0x00007f7f01844ec0 0x000000000174a490

|

+----------------------------------> slots_

gdb-peda$ tel 0x00007f7f01bb18d0 4

0000| 0x7f7f01bb18d0 --> 0x7f7f01b8b0e0 --> 0x2a26380 (:PlainObject::class_>: 0x000000000162a4bf)

0008| 0x7f7f01bb18d8 --> 0x7f7f01bae6c0 --> 0x70000004a # Property Name

0016| 0x7f7f01bb18e0 --> 0xfffe000100000001 # Index in slots_ array is '1' (last 3 bytes)

0024| 0x7f7f01bb18e8 --> 0x7f7f01bb18a8 --> 0x7f7f01b8b0e0 --> 0x2a26380 (:PlainObject::class_>: 0x000000000162a4bf)

|

+-----> pointer to the next shape

# Looking at the property name.

gdb-peda$ x/2wx 0x7f7f01bae6c0

0x7f7f01bae6c0: 0x0000004a 0x00000007 # metadata of the string. 0x4a is flag I think and 7 is the length of string.

gdb-peda$ x/s

0x7f7f01bae6c8: "strtest" # The last property added, is at the head of the linked list.

# The next pointer

gdb-peda$ tel 0x7f7f01bb18a8 4

0000| 0x7f7f01bb18a8 --> 0x7f7f01b8b0e0 --> 0x2a26380 (:PlainObject::class_>: 0x000000000162a4bf)

0008| 0x7f7f01bb18b0 --> 0x7f7f01bae6a0 --> 0x80000004a

0016| 0x7f7f01bb18b8 --> 0xfffe000102000000

0024| 0x7f7f01bb18c0 --> 0x7f7f01b8cb78 --> 0x7f7f01b8b0e0 --> 0x2a26380 (:PlainObject::class_>: 0x000000000162a4bf)

# Name of the property

gdb-peda$ x/xg 0x7f7f01bae6a0

0x7f7f01bae6a0: 0x000000080000004a

gdb-peda$ x/s

0x7f7f01bae6a8: "blahblah"

# The slots_ array

gdb-peda$ x/xg 0x00007f7f01844ec0

0x7f7f01844ec0: 0xfff8800055667788 # index 0 which is value for the property "blahblah"

0x7f7f01844ec8: 0xfffb7f7f01bae6e0 # index 1 which is value for the property "strtest". This is a string object.

# Dereference index 1, which is a pointer to 0x7f7f01bae6e0

gdb-peda$ x/xg 0x7f7f01bae6e0

0x7f7f01bae6e0: 0x0000000a0000004a

gdb-peda$ x/s

0x7f7f01bae6e8: "TESTSTRING"

elements_

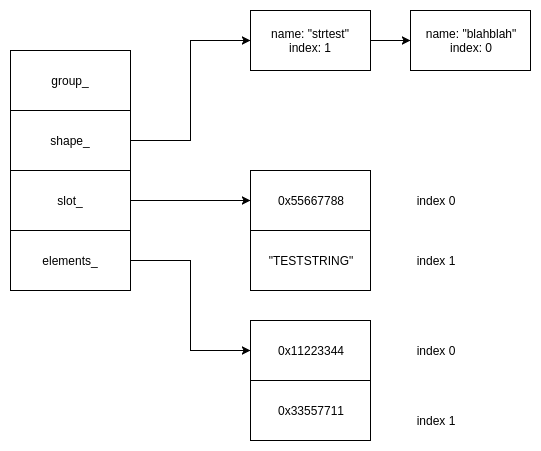

Now in the example that we took in the previous section, the object just had a few properties. What if it had elements as well? Lets add to the above snippet -

1

2

obj[0]=0x11223344

obj[1]=0x33557711

Yep, you guessed it right. The elements are going to be stored in an array pointed to by the elements_ member. Lets take a look at a modified image.

And in gdb -

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

# This time we have all previous pointers plus a pointer to the elements_ array

gdb-peda$ x/4xg 0x7f7f01b90120

0x7f7f01b90120: 0x00007f7f01b8a310 0x00007f7f01bb18d0

0x7f7f01b90130: 0x00007f7f01844ec0 0x00007f7f01844f90 ---> elements_

# The array -

gdb-peda$ x/xg 0x00007f7f01844f90

0x7f7f01844f90: 0xfff8800011223344 # index 0

0x7f7f01844f98: 0xfff8800033557711 # index 0

Now we saw that we can add any number of elements to objects. So the elements_ array has a metadata to keep track of no. of elements etc (This is actually casted to ObjectElements explicitly. Check js/src/vm/NativeObject.h for details). The following constitute the metadata -

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

uint32_t flags;

/*

* Number of initialized elements. This is <= the capacity, and for arrays

* is <= the length. Memory for elements above the initialized length is

* uninitialized, but values between the initialized length and the proper

* length are conceptually holes.

*/

uint32_t initializedLength;

/* Number of allocated slots. */

uint32_t capacity;

/* 'length' property of array objects, unused for other objects. */

uint32_t length;

The above code is from the definition of ObjectElements in NativeObject.h. The comments are self explanatory I guess. Lets add a couple more elements to our obj object…

1

2

obj[2]="asdfasdf"

obj[3]=6.022

…and view this in gdb.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

gdb-peda$ x/4xg 0x7f7f01b90120

0x7f7f01b90120: 0x00007f7f01b8a310 0x00007f7f01bb18d0

0x7f7f01b90130: 0x00007f7f01844ec0 0x00007f7f01844f90

# size of the metadata is 0x10 bytes

gdb-peda$ x/4wx 0x00007f7f01844f90-0x10

Flags init_len capacity length

0x7f7f01844f80: 0x00000000 0x00000004 0x00000006 0x00000000

gdb-peda$ x/4xg

0x7f7f01844f90: 0xfff8800011223344 0xfff8800033557711

0x7f7f01844fa0: 0xfffb7f7f01bae720 0x401816872b020c4a

Typed Arrays

From the MDN page

The

ArrayBufferis a data type that is used to represent a generic, fixed-length binary data buffer. You can’t directly manipulate the contents of anArrayBuffer; instead, you create a typed array view or aDataViewwhich represents the buffer in a specific format, and use that to read and write the contents of the buffer.

All the attribute of the NativeObject are inherited by the ArrayBufferObject. In addition the ArrayBufferObject has the following -

- Pointer to data: Pointer to the data buffer of the ArrayBuffer in the “private” form.

- length: Size of the buffer.

- First View: Pointer to the first view that references the current ArrayBuffer.

- flags

The pointer to the data buffer is stored in the private form, the setPrivate being,

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

void setPrivate(void* ptr) {

MOZ_ASSERT((uintptr_t(ptr) & 1) == 0);

#if defined(JS_NUNBOX32)

s_.tag_ = JSValueTag(0);

s_.payload_.ptr_ = ptr;

#elif defined(JS_PUNBOX64)

asBits_ = uintptr_t(ptr) >> 1;

#endif

MOZ_ASSERT(isDouble());

}

…which is basically this :) -

1

2

3

void setPrivate(void* ptr) {

asBits_ = uintptr_t(ptr) >> 1;

}

Thus it is right shifted by 1. (We’ll check it out in gdb soon)

Now lets create an ArrayBuffer and add a view to this buffer.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

arrbuf = new ArrayBuffer(0x100); // ArrayBuffer of size 0x100 bytes.

uint32view = new Uint32Array(arrbuf); // Adding a Uint32 view.

uint16view = new Uint16Array(arrbuf); // Adding another view - this time a Uint16 one.

uint32view[0]=0x11223344 // Initialize the buffer with a value.

uint32view[0].toString(16)

// Outputs "11223344"

/* Lets check the Uint16Array */

uint16view[0].toString(16)

// Outputs "3344"

uint16view[1].toString(16)

// Outputs "1122"

The different views on the same buffer allow us to look at the data in the buffer in different ways. A TypedArray like an ArrayBuffer has the following extra attributes, in addition to NativeObject

- Underlying ArrayBuffer: Pointer to the ArrayBuffer that holds the data for this typed array

- length: The length of the array. If ArrayBuffer is 0x20 bytes and this is a Uint32Array, length=0x20/4 = 8.

- offset

- pointer to data: This is the pointer to the data buffer in the raw form for enhancing performance.

Lets start looking at how all this is represented in the memory.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

gdb-peda$ x/8xg 0x7f618109a080

0x7f618109a080: 0x00007f618108a8b0 (group_) 0x00007f61810b1a38 (shape_)

0x7f618109a090: 0x0000000000000000 (slots_) 0x000000000174a490 (elements_)

0x7f618109a0a0: 0x00003fb0c0d34b00 (data pointer) 0xfff8800000000100 (length)

0x7f618109a0b0: 0xfffe7f6183d003a0 (first view) 0xfff8800000000008 (flags)

# The data pointer

gdb-peda$ p/x 0x00003fb0c0d34b00 << 1

$2 = 0x7f6181a69600

# The buffer

gdb-peda$ x/2xg 0x7f6181a69600

0x7f6181a69600: 0x0000000011223344 0x0000000000000000

# The Uint32 Array

gdb-peda$ x/8xg 0x7f6183d003a0

0x7f6183d003a0: 0x00007f618108aa30 0x00007f61810b4a60

0x7f6183d003b0: 0x0000000000000000 0x000000000174a490

0x7f6183d003c0: 0xfffe7f618109a080 (ArrayBuffer) 0xfff8800000000040 (length)

0x7f6183d003d0: 0xfff8800000000000 (offset) 0x00007f6181a69600 (Pointer to data buffer)

# The Uint16 Array

gdb-peda$ x/8xg 0x7f6183d003e0

0x7f6183d003e0: 0x00007f618108aaf0 0x00007f61810b4ba0

0x7f6183d003f0: 0x0000000000000000 0x000000000174a490

0x7f6183d00400: 0xfffe7f618109a080 (ArrayBuffer) 0xfff8800000000080 (length)

0x7f6183d00410: 0xfff8800000000000 (offset) 0x00007f6181a69600 (Pointer to data buffer)

Since the data in the TypedArrays are saved without nan-boxing and as the C native types, this is really useful in exploitation, where we might feel the need to read and write data to and from arbitrary location. Now, imagine that you have control over the data pointer of an ArrayBuffer. Thus you can read and write 4 bytes at a time, to and from an arbitrary location by assigning a Uint32Array with the corrupted ArrayBuffer. If, instead, we use a normal array for this then the data read from arbitrary location would be in float and to write data to the location we would need to give the payload in float instead of int.

Epilogue

So that kind of summarizes what I have learned so far :). When I get some more free time I plan to write a writeup for blazefox which is a pretty easy challenge and a really good one to try out for starting with browser related exploitation.

I know that this is still incomplete and probably error ridden. If you spot any mistake in the post I would be glad to correct it.